Why Israel Beat the US in the Laser Weapon Race

The Israeli military’s 'Iron Beam' laser weapon is about to officially enter service.

Israel is about to pull off a feat the United States has been dreaming of for years: the official fielding and deployment of a high-energy laser weapon.

Israeli defense giant Rafael announced last week that it had completed final tests of its 100 kilowatt ‘Iron Beam’ laser weapon system, which “concludes the development phase and represents the final milestone before delivering the system” to the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) for a “formal operational deployment.”

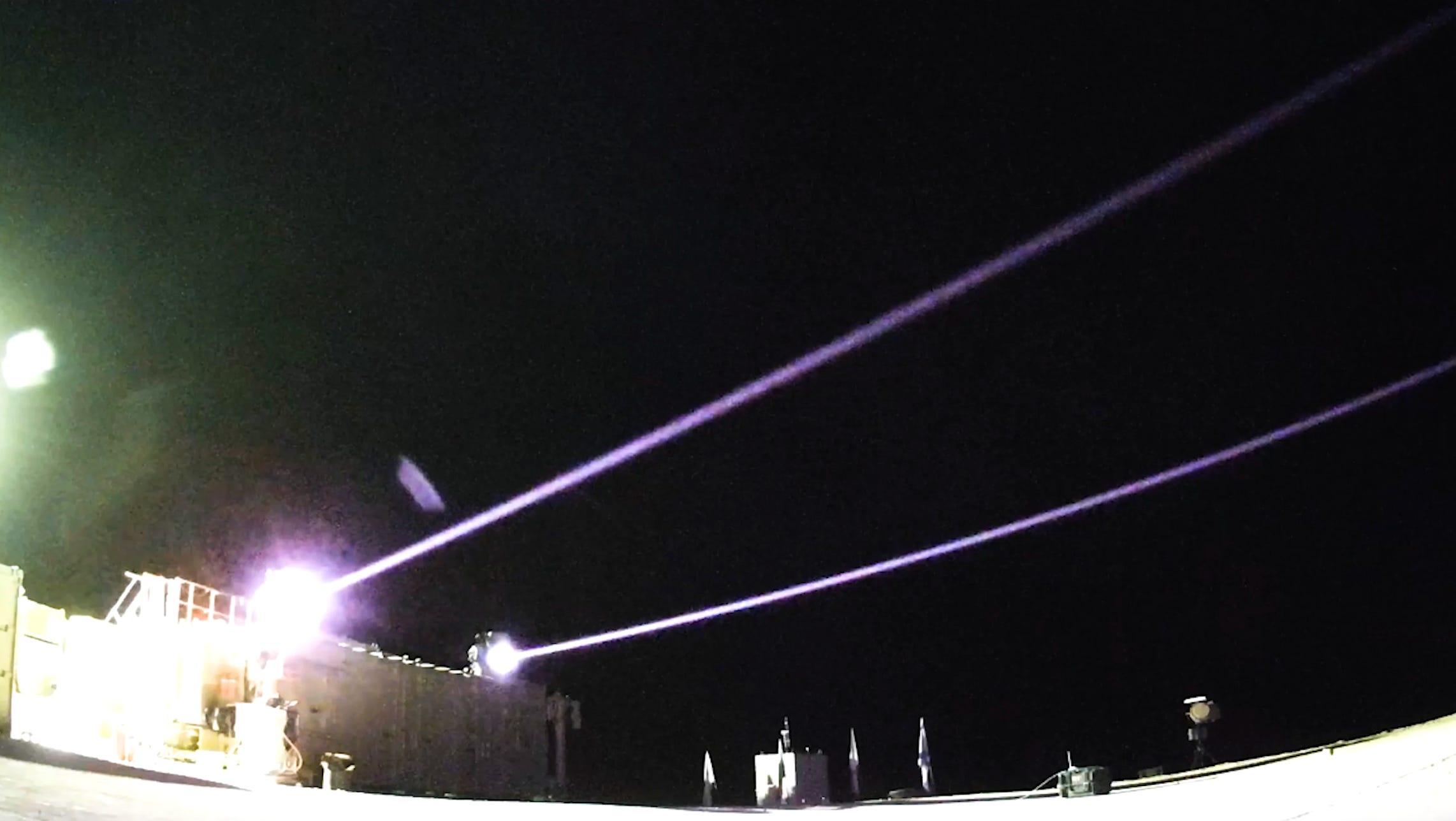

Watch Israel’s ‘Iron Beam’ in action during testing:

The announcement was met with significant fanfare, and with good reason. While the IDF previously used several lower-powered Iron Beam prototypes to neutralize drones launched by Hezbollah fighters during Israel’s October 2024 invasion of Lebanon, the upcoming deployment marks the first time a fighting force will actively employ fully mature laser weapons for air defense. (By comparison, the two 20 kw Palletized High Energy Laser (P-HEL) systems the United States military sent downrange in the last few years were mere prototypes, according to a recent US Army presentation.)

“Achieving operational laser interception capability places the State of Israel at the forefront of global military technology and makes Israel the first nation to possess this capability,” Defense Minister Israel Katz said in a statement. “This is not only a moment of national pride, but a historic milestone for our defense envelope: rapid, precise interception at marginal cost that joins our existing defense systems and changes the threat equation.”

In development since at least 2014, the Iron Beam’s official integration into Israeli formations represents a watershed moment for the development of directed energy weapons. It’s also somewhat embarrassing for the US Defense Department, which has struggled to transition its laser weapons programs out of the lab for decades despite investing nearly $1 billion annually in their development. The Pentagon has been shooting down drones with lasers since 1973 — why is it so difficult to actually get them onto the battlefield, and how did Israel manage to pull it off?

The short answer is that Israel builds weapons differently — with more urgency, fewer bureaucratic hurdles, and a focus on progress over perfection.

Israel has lived under daily threat for most of its existence. Regular rocket and drone attacks from Gaza, Lebanon, and elsewhere have made defense tech rapid innovation a survival imperative. As US Marine Corps Maj. Joshua Fernandez writes in a 2024 Naval Postgraduate School analysis, this has made Israel’s defense procurement system inherently threat-driven, with priorities and timelines directly influenced by immediate operational danger rather than theoretical future scenarios. And this urgency has become even more pronounced with the rise of low-cost weaponized drones as a defining feature of modern warfare. Every Tamir interceptor fired from Iron Dome missile defense screen can cost between $20,000 to $100,000, while the targets they intercept may cost as little as $500 — an asymmetric cost pressure that Israel cannot sustain indefinitely.

The constant threat of attack is exactly why Iron Beam leapt from prototypes to emergency use in the 2024 Lebanon campaign ahead of its formal operational deployment this year. According to a May interview with the (anonymous) head of the Israeli Air Force’s laser division, Rafael “launched an accelerated development process” alongside the MoD in the aftermath of the October 7, 2023 attack on the country, “incorporating various adaptations that enabled us to deploy a laser system in unprecedented time frames.” Necessity, as the proverb goes, is the mother of invention.

By contrast, the US faces no equivalent rocket or drone threat on its homeland (although that risk is certainly growing). While demand for such systems among US military leaders has increased significantly amid the Iran-backed Houthi drone and missile attacks in the Red Sea, the lack of constant danger makes it far easier to slow-roll or cancel programs; without the presence of significant external pressures (like the specter of annihilation) to incentivize innovation and adaptation, technological progress stagnates.1 It also doesn’t help that the US operates under a rigid Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE) system, which separates planning from implementation by years and leaves little room for speed or improvisation — a process that a 2024 report on PPBE reform warned is increasingly unfit for modern defense innovation.

Israel’s organizational approach to military innovation is also a significant factor. The country’s defense ecosystem is small and tightly coordinated, with the MoD, the IDF, and industry partners like Rafael deeply aligned to ensure that research and development and operational feedback are closely coupled. This is a deliberate feature of the Israeli national security apparatus: as military strategists and historians Edward Luttwak and Eitan Shamir argue in The Art of Military Innovation: Lessons from the Israel Defense Forces, the IDF has enjoyed a uniquely unified structure since its inception, which in practice means that R&D funds are not parceled out to the separate services with overlapping (and often competing) missions and priorities. In the US, multiple services and organizations run their own projects and navigate Pentagon bureaucracy, congressional oversight, and extended R&D budget cycles without significant coordination, resulting in a slower and less cohesive approach for an acquisition ecosystem that already struggles to field urgent capabilities at speed.

Israel’s close-knit defense ecosystem is also reinforced at the human level. As US Air Force Col. George Dougherty observed in a 2020 analysis in Joint Force Quarterly, the elite “Talpiot” program Israel established in 1979 aggressively trains recruits as both technologists and combat officers, with graduates acting “as the glue between Israel’s operational military and defense technology communities … [with] a firsthand understanding of both the military requirements in the field and the applicable science and technology.” Talpiot embeds innovation into the IDF’s leadership pipeline, reflecting Israel’s concerted effort to shorten the distance between the lab and the battlefield for high-impact defense tech like, say, the Trophy Active Defense System. By comparison, the US maintains clearer divides between operators and technologists, which can widen the gap between R&D and operational need — a problem that the American tech sector and defense establishment have only recently started to address.

“Military technology leaders in the United States have sometimes dreamed of a situation in which the top talent in Silicon Valley dedicate themselves to military innovation for the benefit of the country’s defense,” Dougherty writes. “That situation is the norm in Israel.”

This organizational structure and culture mean the IDF is primed to favor disruptive “macroinnovations” — weapons or techniques that did not previously exist — not just due to an abundance of technical talent but because no entrenched service branches exist to block radical change. The Art of Military Innovation points out that this coordinated approach has yielded a long history of defense tech breakthroughs for Israel, from the development of the Gabriel sea-skimming anti-ship missile that proved critical during the 1973 Yom Kippur War to the pioneering use of remotely piloted vehicles (i.e. drones) that same decade. This is a sharp contrast to the US military, where deeply institutionalized services that are compliance-driven and risk-averse often favor incremental upgrades to legacy platforms and interservice rivalries can stifle disruptive technologies that threaten established budgets and missions.2

Together, the threat environment and unique organizational structure and culture yield two particular advantages, according to the NPS analysis: a high risk tolerance to prioritize schedule over performance and quicker approval process due to limited oversight. These factors create a military acquisition ecosystem ripe for rapidly prototyping and field-testing new tech for which the IDF may not even have formal requirements yet. As Dougherty notes in his Joint Force Quarterly analysis, the Israeli MoD’s emphasis on operational demonstrators in particular plays a key role in not just refining technical elements, but cultivating support for untested technologies (the Iron Dome, for example, was deployed in 2011 during an active rocket barrage while still in its demonstrator phase). Where next-generation Pentagon systems often end up trapped in the “valley of death” between R&D and adoption due unclear transition pathways or a lack of political buy-in, Israel simply “cannot afford to let potentially impactful advances languish” in acquisition limbo, as Dougherty puts it. The IDF doesn’t wait for perfection: it deploys systems that are “good enough,” then learns and iterates in combat.3

The differences are clear. Israel faces daily aerial threats and has developed fast, centralized pathways and a culture of innovation.to counter them. The US may have more money, labs, and programs, but it also face fewer immediate threats, buries its initiatives in bureaucracy, and waits for perfection before transitioning new technologies to the battlefield. That’s why Iron Beam is rolling into IDF service while American laser weapons remain prototypes: Israel’s advantage lies not just in engineering, but an organizational culture.

From Iron Dome to Iron Beam, Israel has rewritten the playbook of air defense — a reminder that necessity, not size, drives military revolutions. The only question now is whether the US can catch up.

✉️ Thought this analysis was total garbage? Have additional information you’d like to recommend? Want to tell me to go fuck myself? Drop me a line:

Consider this a defense tech equivalent of environmental historian Mark Elvin’s concept of a “high-level equilibrium trap.” The theory posits that China never experienced its own version of the Industrial Revolution due to its relative wealth and stability while the United Kingdom endured significant scarcity and inefficiency, economic challenges that spurred scientific and engineering advances to address them and triggered a tectonic shift from an agrarian society to an industrial one. Noah Smith articulated this nicely in the The Week in 2015: “When a country thinks it's in a golden age, it stops focusing on progress.” (For more on this, I recommend economic historian Kenneth Pomeranz’s fantastic 2000 book The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy.)

If Israel is a “start-up nation,” as Joint Forces Quarterly describes it, then its motto is probably something along the lines of “fuck it, ship it.”