The Second Life of the Pentagon’s Magic Bullet

The US military's Hypervelocity Projectile is steadily inching towards combat.

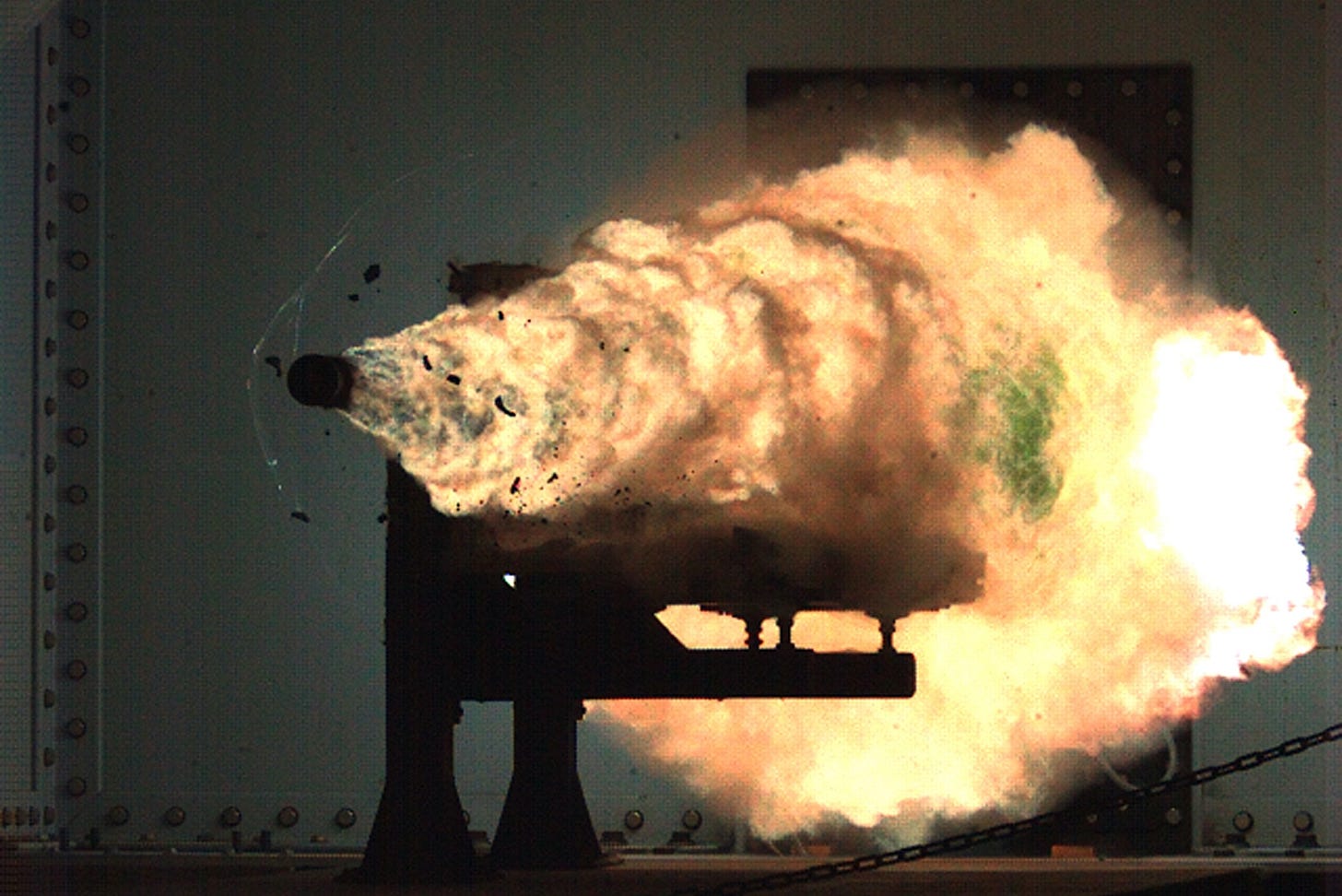

For nearly two decades, the US Defense Department chased a tantalizing dream that never quite panned out: an electromagnetic railgun capable of firing projectiles …