The Pentagon's Looming Laser Weapon Supply Chain Problem

Critical minerals may be the most significant barrier to rapidly scaling high-energy laser weapons across the US military.

After decades of research and development, the US military is kicking its efforts to field mature high-energy laser weapons into high gear.

In November, the US Defense Department unveiled an updated list of critical technology areas, cutting-edge technologies that military leaders see as essential to maintaining dominance against adversaries for a new era of rapid innovation. Those areas included what the Pentagon calls “scaled directed energy” — a focus on evolving its current arsenal of high-energy laser and high-powered microwave weapons from exquisite prototypes to mass-producible systems ready for field deployment. Amid the convergence of significant technological advancements and unprecedented institutional support, American laser weapons appear poised to finally make the jump from lab to battlefield.

But there’s a hard truth about America’s directed energy ambitions on the horizon: the Pentagon may soon find itself unable to actually build these systems at the scale it envisions.

This isn’t because of technological hurdles or bureaucratic obstacles, but a brutal collision of geopolitics and logistics. The Pentagon’s annual report to Congress on China’s military capabilities published on in late December contains a brief but essential warning that Beijing currently maintains a stranglehold on the supply chains for critical minerals necessary to mass produce laser weapons.

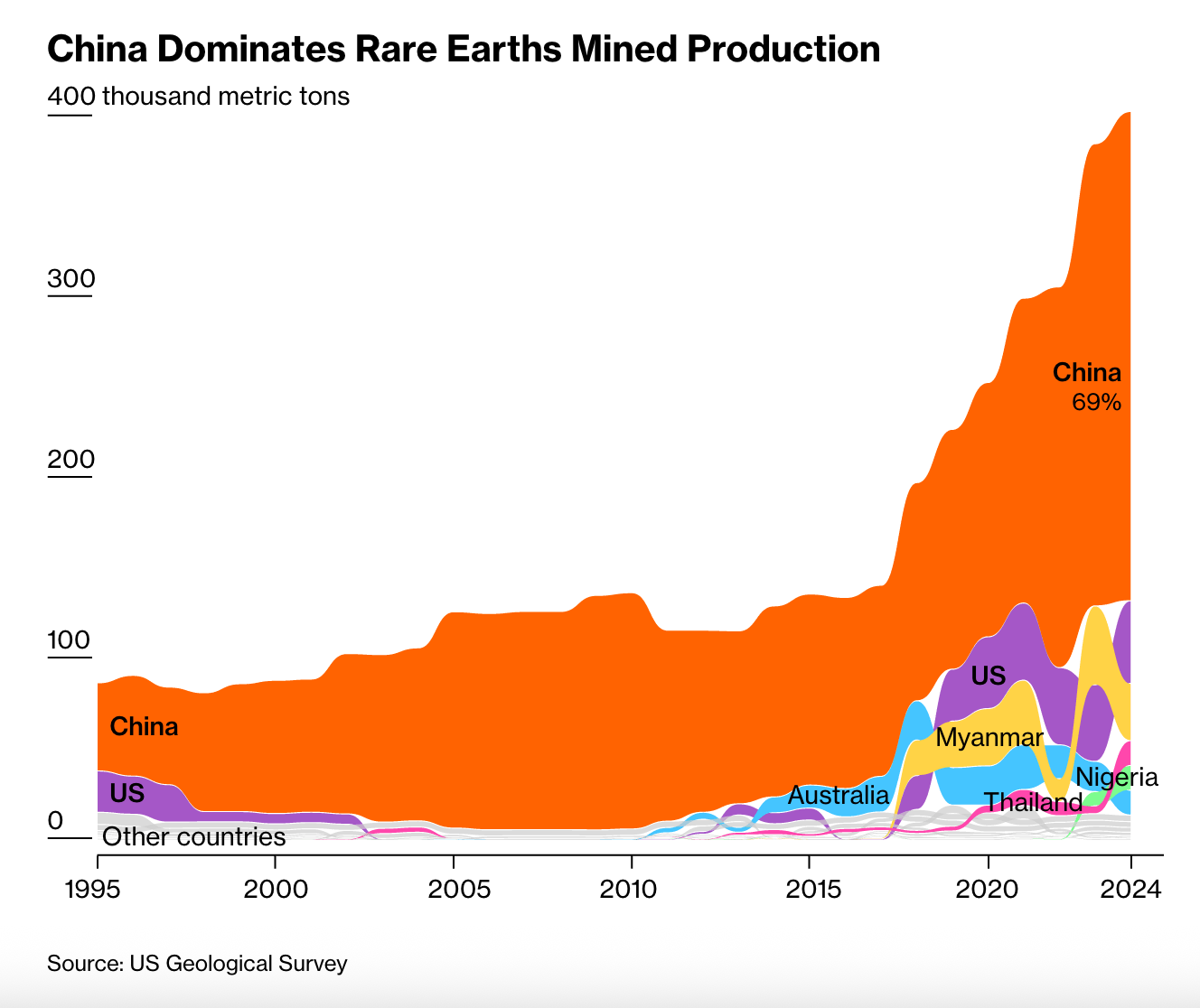

China produces more than 60% of the world’s rare earth elements — a group of 17 metals used in essential defense technologies from munitions to tanks — and processes nearly 90% of the global supply, according to a 2021 International Energy Agency (IEA) report. This monopoly extends to other critical minerals as well, giving Beijing a potent economic tool to achieve its geopolitical objectives without resorting to direct military action. China’s market domination doesn’t just have long-term ramifications for the US defense industrial base’s ability to churn out directed energy weapons at wartime levels, but “partially contribut[es] to Beijing’s domestic capacity to unilaterally develop and produce such weapons” as aggressively as it has in recent years, the report says. When it comes to the foundational building blocks of laser weapons, China has a clear material advantage.

As a result, supply chain vulnerabilities may prove a deciding factor in whether American laser weapons ever actually transition from unique to ubiquitous. A comprehensive 2024 report from the National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA) trade group on directed energy weapon supply chains detailed the major chokepoints the US military current faces. While the report is worth reading in full, here are the key elements relevant to laser weapons.1

Lasing Medium and Doping Materials

A lasing medium is a critical component of laser weapons, responsible for amplifying light through stimulated emission to produce a concentrated beam capable of destructive effects. Because solid gain media like crystals or glass are essential for solid-state and fiber lasers, doping materials (think trace impurities) are carefully introduced during processes like crystal growth to improve stability and optical quality, thereby boosting a system’s power output and efficiency

According to the NDIA report, the doping agents used in laser weapons are primarily rare earth elements like neodymium, erbium, thulium, and ytterbium, and the US relies on China for the mining and processing of all of them. Indeed, US Geological Survey data indicates that Chinese exports accounted for 74% of US rare earth element imports between 2018 and 2021, while Beijing controls more than 85% of the world’s processing capacity.

The report notes that the while US government made investments to onshore rare earth processing capabilities to reduce dependence on China in recent years, it concludes that US capacity will remain insufficient to support the rapid production of directed energy weapons in the near term even.

Laser Diode Pumps

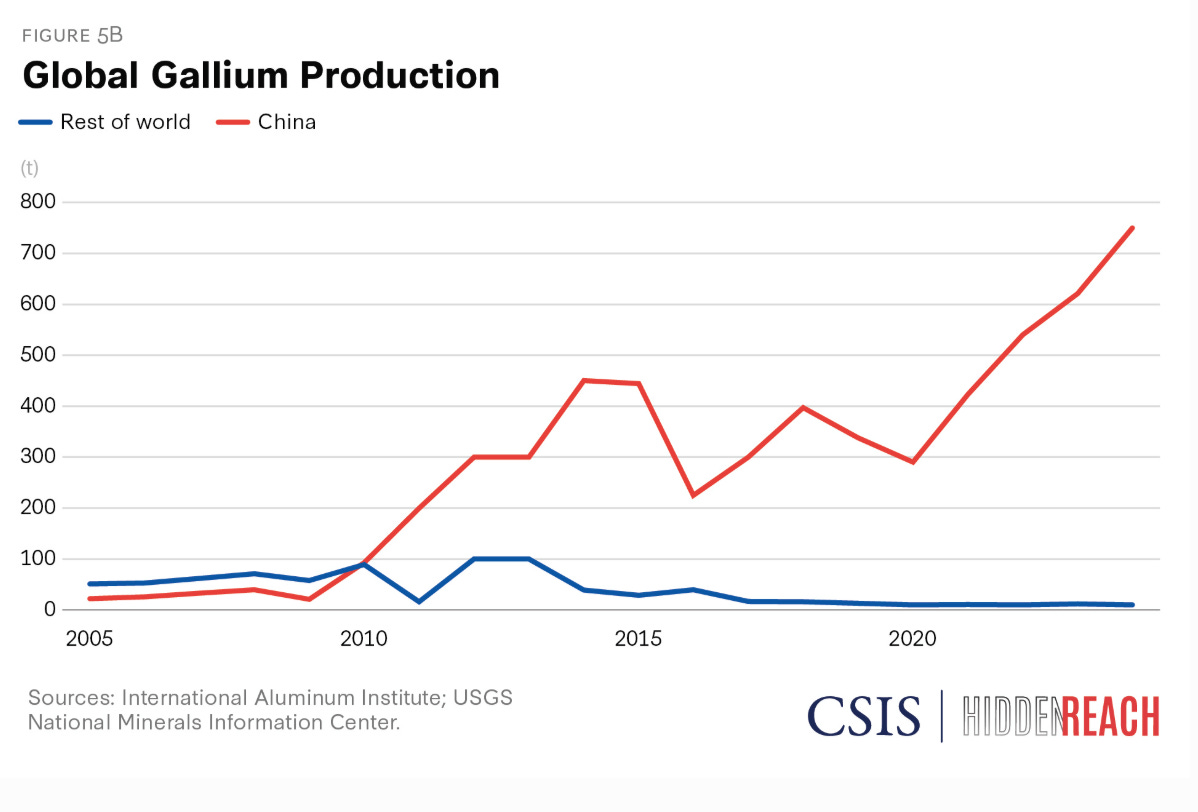

Laser diode pumps are the enabling backbone of modern solid-state laser weapons, providing the electrical-to-optical energy conversion that excites the lasing medium. These diodes are overwhelmingly based on gallium compounds (namely gallium arsenide) which offer the efficiency, durability, and wavelength specificity required for military laser weapons.2 The NDIA report states that 74% of gallium in the US is used for integrated circuits, followed by 25% for optoelectronic devices like laser diodes and just 1% for research and development.

Gallium is a critical vulnerability in the directed energy supply chain. As of 2023, the US was importing 53% of its gallium from China, which controls 98% of the global market. This vulnerability has become increasingly pronounced as Beijing has ratcheted up export controls3 on gallium and, more recently, unveiled (and then temporarily paused) an outright ban on exports to the US. Because pump diodes cannot be readily substituted or stockpiled at scale without significant performance challenges, even modest disruptions in gallium exports could significantly constrain US production of laser weapons.

Not only does the US government lack a strategic gallium stockpile, but domestic production is restricted to a single New York-based company, Indium Corp, despite the looming ban on Chinese exports to the country. However, the NDIA report does note that China’s dominance of the gallium market is a relatively recent (circa 2011) development, and that Beijing’s export controls may end up inducing past sources like Germany, Canada, and Ukraine to restart production in response.

Optics and Beam Control

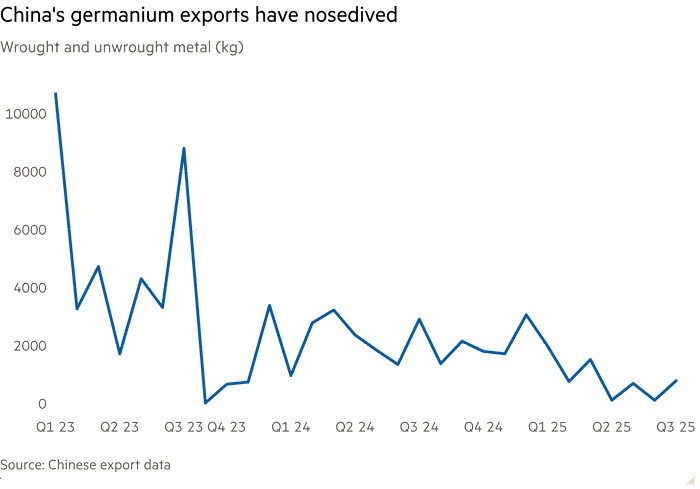

Beyond generating power, laser weapons depend on precision optics to focus, sustain, and amplify a beam under combat conditions. Germanium plays a central role in this layer of the system architecture, particularly in infrared optical components such as lenses, windows, and beam-control assemblies used for targeting and atmospheric compensation.

The NDIA report notes lasers that operate at wavelengths other than infrared tend to depend on more conventional glass for these functions and therefore tend to sidestep significant supply chain issues (although they still sacrifice range, power, or atmospheric performance). But as with gallium, the US remains heavily dependent on foreign sources for refined germanium, with 54% of its imports coming from China as of 2023 and Beijing instituting fresh export controls on both critical minerals in the middle of that year.

This creates a subtle but consequential bottleneck: without reliable access to advanced optical materials, increases in raw laser power do not translate cleanly into battlefield-relevant capability.

Thermal Management

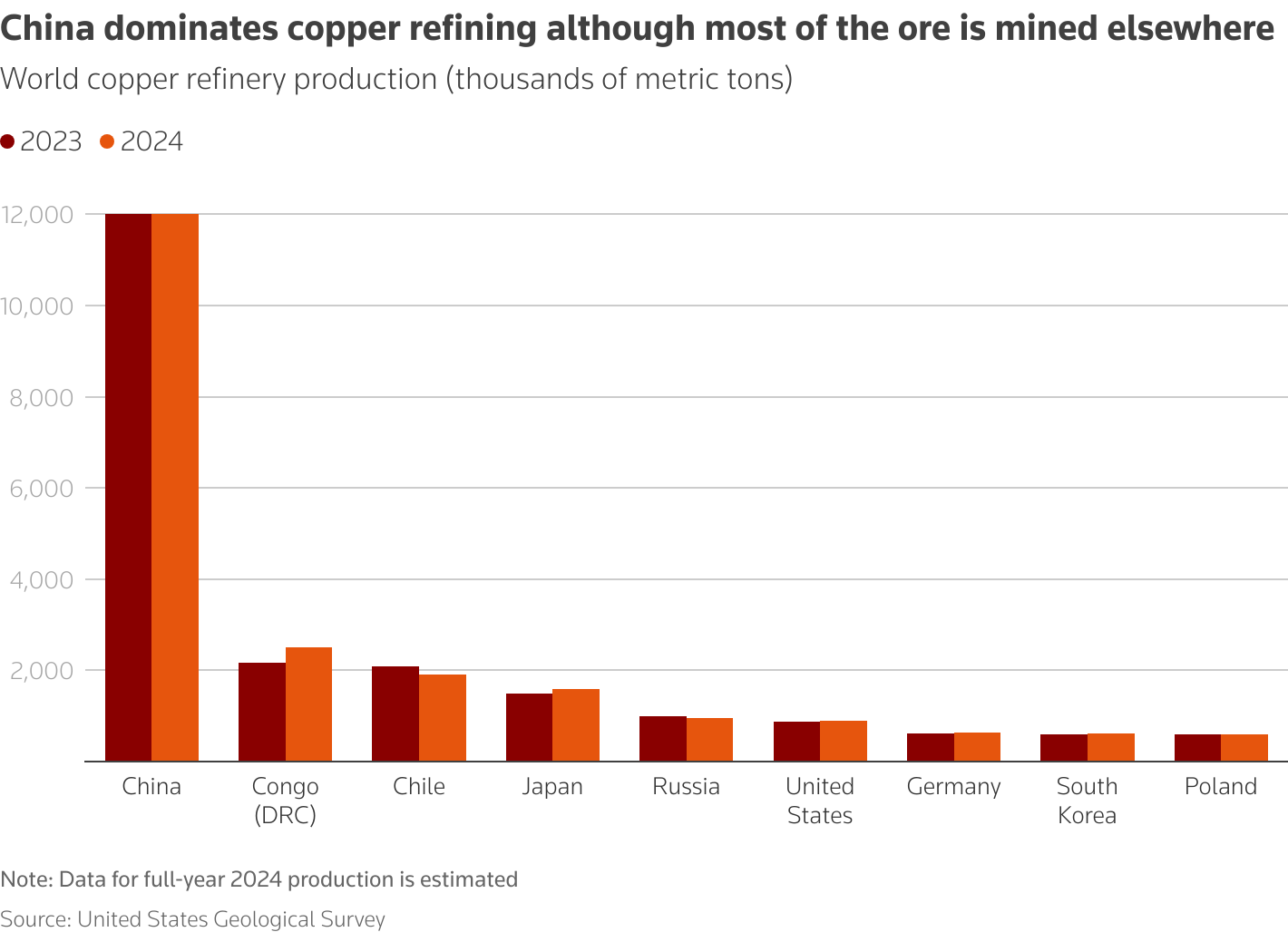

Thermal management is one of the most underappreciated constraints on scaling directed energy weapons, and copper sits at the center of this challenge. High-energy lasers generate a significant amount of heat that must be rapidly dissipated to prevent degradation, misalignment, or catastrophic system failure, and copper’s exceptional thermal conductivity makes it indispensable for heat sinks, cold plates, power electronics, and beam-control subsystems across system designs.

The NDIA report notes that while copper is not scarce in a geological sense for the US, which is the world’s fifth largest producer, the process of transforming copper into the refined form required for advanced defense applications is subject to industrial concentration and geopolitical pressure. As of 2022, 41% of all refined copper originated in China, partially due to the fact that Beijing possessed 14 copper smelters at the time compared to a paltry trio in the US.

This problem will only grow more acute as US copper demand accelerates in coming years: Washington’s needs are projected to grow to three times the global supply by 2035 despite an anticipated 6.5 million ton shortage by 2030, according to the NDIA report. As laser weapons scale in power and duty cycle, thermal management will become more of a material problem rather than a design one.

Crucially, the NDIA report makes clear that the Pentagon can’t simply engineer a solution around these supply chain challenges. Fiber and solid-state lasers concentrate vulnerability in rare earth dopants and gallium-based pump diodes. Infrared systems shift dependence toward germanium-intensive optics and beam-control components. Meanwhile, designs optimized for higher power levels and sustained firing cycles disproportionately rely on copper-heavy thermal management subsystems. There is no “safe” laser architecture: each design choice trades one constrained material for another, leaving the Pentagon’s broader ambitions exposed to the export control decisions of Beijing regardless of which systems ultimately prevail in the US military procurement process.

Compounding this challenge is the absence of meaningful substitutes for many of these materials. Rare earth dopants are selected for highly specific wavelength, efficiency, and thermal properties that cannot be replicated with more abundant elements. Gallium compounds dominate high-efficiency laser pumping because alternative semiconductors fail to deliver comparable power density or durability. Germanium’s infrared transparency and refractive characteristics remain unmatched for high-power optical applications. Finally, copper’s thermal conductivity makes it uniquely suited for managing the extreme heat generated by modern laser weapons. Physics matters at least as much as industrial inertia, if not more.

Taken together, these factors foreshadow trouble ahead for the Pentagon’s scaled directed energy push. The limiting factor is no longer whether laser weapons work (they do) or even whether the US military wants them (it does) – it’s whether the industrial ecosystem required to build them can survive material scarcity and geopolitical pressure. Directed energy, long framed as a solution to the cost and logistics problems of modern drone warfare, may ultimately inherit those same constraints at the system level. Until these challenges are addressed, the Pentagon’s vision of deploying laser weapons at scale will remain constrained by material reality.

I would be remiss if I didn’t note that the physical sciences have never been my strongest subject. If you see an error in this analysis, please send a sternly worded letter here.

As I previously reported for Fast Company, gallium nitride is also a key component of the high-powered microwave weapons the US Army recently purchased from defense contractor Epirus.

The export controls mean that the Chinese government now directly approves exports of both gallium and germanium “for national security reasons.” According to the NDIA report, approving the licenses necessary for exporters can take months.