The Army Finally Has a Real Path to Fielding Laser Weapons

A draft request for proposal details a requirement to “produce and rapidly field” up to 24 Enduring High Energy Laser systems.

The US Army is finally getting serious about putting high-energy laser weapons in the hands of American soldiers.

In a new draft request for proposal (RFP) published on January 21, the Army’s Portfolio Acquisition Executive Fires1 laid out a requirement to “produce and rapidly field” up to 24 next-generation Enduring High Energy Laser (E-HEL) systems to counter hostile drones, a rare sign that the service’s directed energy efforts are moving from prototyping and into a real acquisition timeline.

The contract proposed in the draft RFP is structured as a production ramp, with two systems up front followed by additional batches as options, plus spares and support work baked in. The contract would also cap total duration at 66 months,2 an indication the service expects E-HEL system to mature on a near-to-mid-term timeline rather than staying trapped in perpetual experimentation. If all goes according to plan, E-HEL will become the service’s first directed energy program of record.

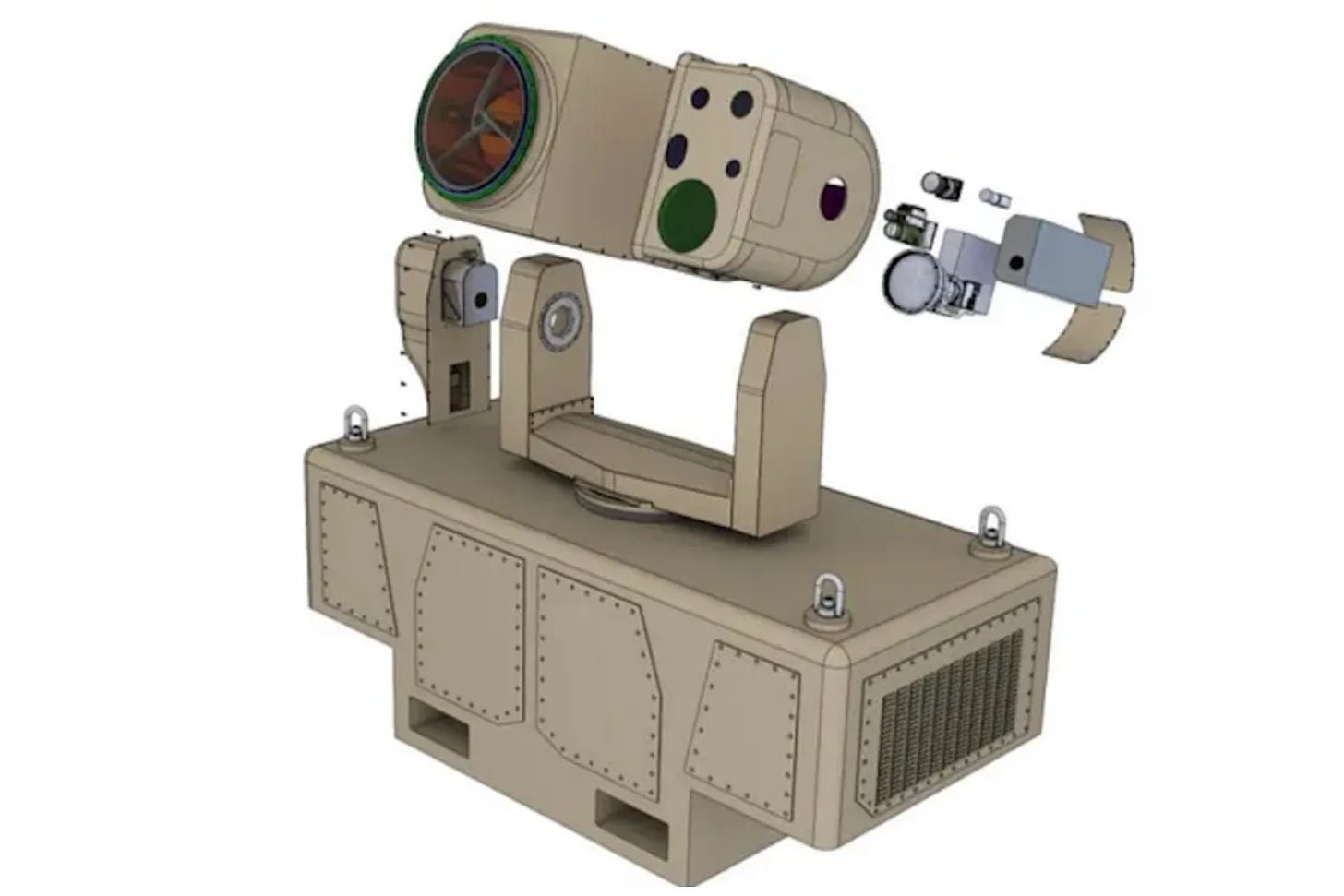

First unveiled in a July 2024 special notice, the Army envisions E-HEL as a modular system that leverages design and sustainment lessons from previous laser weapon efforts. Those include the Stryker-mounted 50 kilowatt Directed Energy Maneuver-Short Range Air Defense (DE M-SHORAD) system, which a Government Accountability Office report published in June 2025 determined was “not mature enough” for duty, and the 20 kw Palletized-High Energy Laser (P-HEL) system, which has watched over soldiers overseas in recent years.

The underlying driver is obvious: drones have become a cheap and effective way to rain violence down upon adversary forces, and traditional air defenses simply can’t afford to shoot down attritable targets with million-dollar interceptors forever. Indeed, the US Defense Department is increasingly focused on directed energy weapons like lasers as critical capabilities for American forces facing a future conflict shaped by unmanned systems.

Here are some of the key factors that the Army plans on using to evaluate proposed E-HEL solutions, according to the draft RFP:

Demonstrated Lethality: Range-proven hard-kill capability against Group 1 and Group 2 one-way attack drones, as well as standard Group 3 systems3 – more specifically, the ability to deliver at least 1 kw per square centimeter of irradiance onto targets up to four kilometers away

Sustained Full-Power Operation: Ability to maintain a minute of continuous lasing at full power without damaging the weapon system

Engagement Profile Performance: Three distinct engagement profiles: 30 one-second shots a minute in high target density scenarios, six nine-second shots a minute in low target density scenarios, and three 17-second shots a minute against hard targets

System Recharge: Recharge cycle of no more than four minutes, during which the system “shall recover the magazine to original conditions”

Foreign Object Damage Mitigation: Design that effectively prevents foreign object damage during real-world operations

Interoperability: Must seamlessly integrate with US military command and control systems like the Army’s Integrated Battle Command System-Maneuver (IBCS-M) and other open-architecture networks

Vehicle Integration: Must integrate with the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV) without jeopardizing the vehicle’s transportability and maneuverability requirements

Production Readiness and Capacity: Manufacturing facilities capable of supporting both concurrent and surge production of systems

The most interesting evaluation factors in the draft RFP (to me, at least) are the engagement profiles and recharge cycle. With the engagement profiles, the Army is describing a system designed to adapt to various combat scenarios: fast shots for high target density moments and longer burns for harder targets, both with a relatively short recovery window (two seconds between individual shots, per the RFP) before the system returns to “ready” condition. This reflects the brutal reality of drone warfare, where saturation attacks require rapid and repeated action to effectively counter. But it’s also a reminder that sustained laser weapon performance is a function of dwell time, or the number of seconds a beam has to stay on target to achieve desired effects – and when facing off against a drone swarm on a chaotic battlefield, a nine- or 17-second shot can feel like an eternity.

This is compounded by the four-minute recharge cycle. This isn’t as much a tactical hiccup as it is a technical challenge to the long-running argument that laser weapons offer an “unlimited magazine” — that is, that they can engage targets without ever needing to reload as long as they have a consistent power source. The recharge constraint upends this logic: while a laser weapon may not need to physically change magazines, its output is limited by factors like power and thermal management. For example, Australian defense contractor Electro Optic Systems’ 150 kw “Apollo” laser weapon is advertised as capable of roughly 200 shots on its internal magazine, according to the company. When considered alongside the dwell time issue, the implication is clear: ammo may not be a major problem, but physics and time certainly are.4

Still, the draft RFP indicates a pivotal moment ahead for the Army’s directed energy ambitions. For years, the service’s laser weapon story has been stuck in a loop of promising demonstrations followed by a long slog of integration and adoption problems that keep systems from evolving into operational capabilities soldiers can actually rely on. The draft RFP suggests the service is trying to break out of that cycle, laying out a production ramp designed to keep E-HEL viable long after delivery. Instead of chasing yet another exquisite prototype, the service now appears ready to lay out a pathway to produce and maintain laser weapons at scale.

There’s also actual money and a tentative timeline behind this ambition. The Army’s fiscal year 2026 budget request included $49.75 million for the procurement of “up to two” E-HEL systems and $11.13 million in related research and development funding. The service had previously planned on taking delivery of its first E-HEL prototype by the second quarter of fiscal year 2026 following scheduled demonstrations in January, with production units slated to begin delivery to the service by the end of fiscal year 2027. Should E-HEL prove wildly successful during future testing, the Army will likely have a company’s worth of E-HEL systems at its disposal by some time in the early 2030s.

At the moment, there are two known contenders to produce E-HEL systems: Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII), which received a $14.82 million contract for system design work in February 2025, and AV (formerly AeroVironment and Blue Halo), which in August 2025 unveiled an upgraded version of the LOCUST Laser Weapon System designed specifically for the E-HEL competition. While HII, traditionally a shipbuilder, has never built a laser weapon before,5 AV’s LOCUST has already traveled overseas as the P-HEL and currently adorns a handful of JLTVs and Infantry Squad Vehicles as part of the Army Multi-Purpose High Energy Laser (AMP-HEL) initiative.

Of course, none of this guarantees that E-HEL will succeed. Laser weapons programs tend to die the same way: through power and heat management challenges, integration headaches, and the unpredictable challenges of field conditions. Making a laser work in a controlled test environment is one thing, but the real challenge is actually keeping the system operational under real-world conditions.

After years of hype, the E-HEL draft RFP indicates that the Army is trying to operationalize laser weapons. If the service can actually translate its stated evaluation criteria into a real production contract and fielded units, E-HEL will mark the beginning of laser weapons as a routine part of Army air defense — less a moonshot and more an overdue solution to the challenges of modern drone warfare. And with Pentagon support for directed energy capabilities at its highest point in recent memory, the service may finally have the opportunity to pull it off.

Read the entire E-HEL draft RFP below:

Established in November 2025 through the merger of the Army’s Rapid Capabilities and Critical Technologies Office and the Program Executive Office Missiles and Space as part of major overhaul of the service’s acquisition structure.

Like Josef Stalin and Mao Zedong, the Army apparently has a five-year plan for fielding laser weapons (or five-and-a-half year plan, if you want to be precise).

Group 1 drones weight up to 20 pounds, Group 2 drones weigh between 21 and 55 pounds, and Group 3 drones weight between 56 and 1,320 pounds, according to the Defense Department’s definitions.

More on the myth of the unlimited magazine in a future edition of Laser Wars.

That we know of.