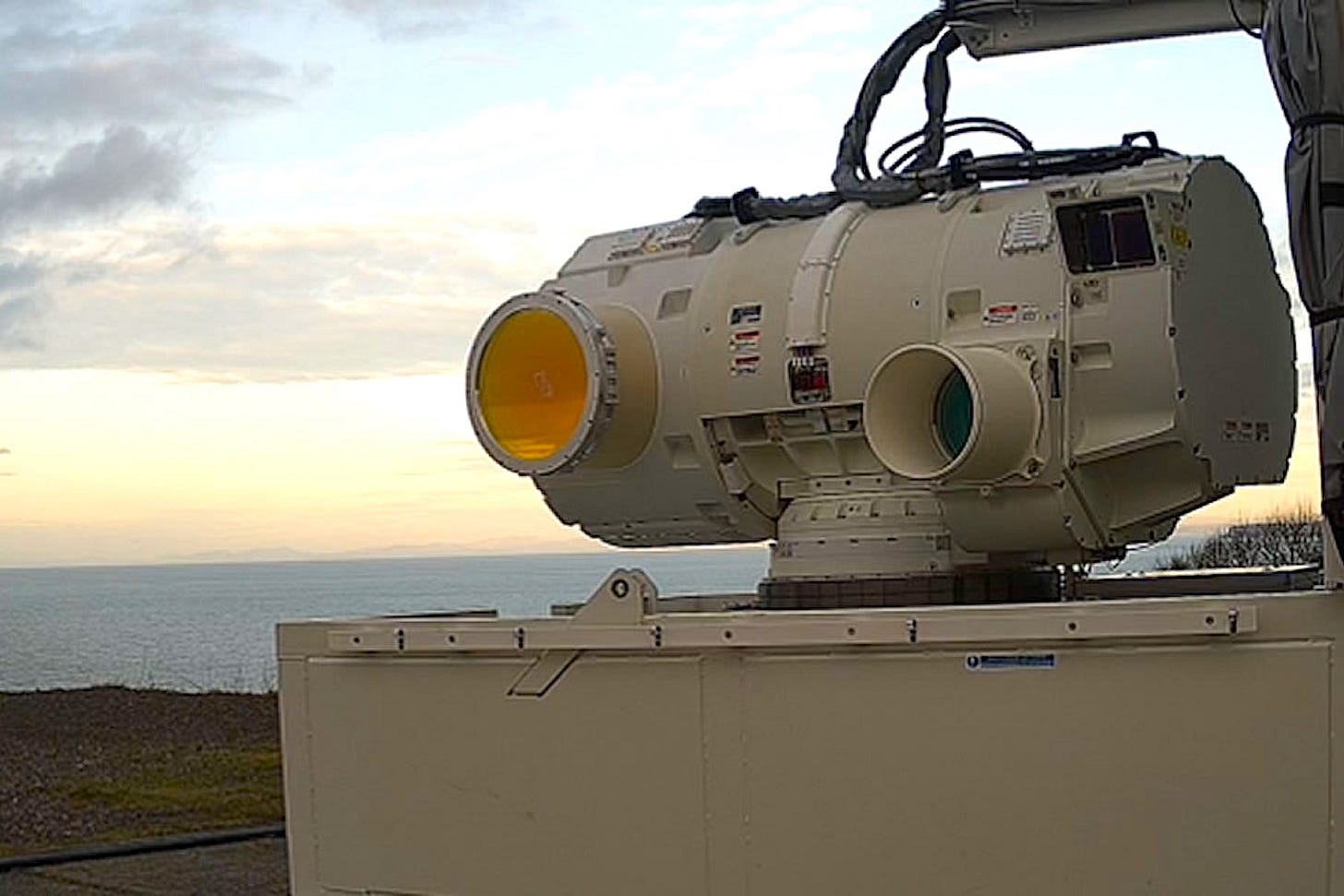

The Royal Navy’s 'DragonFire' Laser Weapon Downs 30 Drones in Trial

The UK’s 50 kilowatt laser weapon system is inching closer to deployment amid rising investment in directed energy.

The UK Royal Navy’s primary laser weapon is edging closer to operational deployment, according to a recent statement from the government's top defense procurement official.

In a written response to a question British MP James Cartlidge published by Parliament in lat…