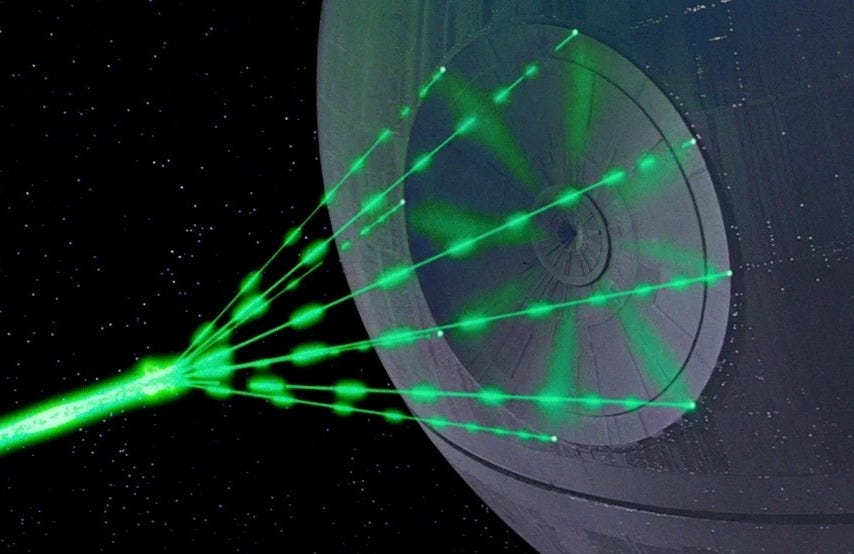

The US Military Officially Wants Laser Weapons For Its ‘Golden Dome’ Missile Shield

A new Joint Laser Weapon System is in the works to defend the US against cruise missile threats.

More than 40 years ago after President Ronald Reagan promised Americans a space-based laser shield straight out of “Star Wars” to end the era of nuclear brinkmanship, the United States is finally getting its directed energy missile defense — sort of.

The Trump…